Propeller System

Image Gallery

Research

Alignment

- With one person in the cabin adjusting the mounting bolts, another should position [themselves] under the cockpit where [they] can see the coupling and call out instructions to raise or lower. By rotating the shaft with your hand, you can see where the two coupling halves begin to kiss one another. When all four coupling halves begin to kiss one another. When all four couping flanges barely touch is a near-perfect alignment. Hunker down on the engine mounting bolts so that nothing can vibrate out of place. While a feeler gauge is the traditional method, an easier way is to insert a piece of paper between the two couplings and study the imprints and grease markings for uniformity. (Upgrading the Cruising Sailboat, p. 147)

Cutlass Bearing

- The cutlass bearing is therubber-surfaced insert through which your shaft runs…be warned that these eventually wear, especially with a lot of use. Wear can cause vibration severe enough to do damage. We usually check ours by diving, grabbing the shaft, and shaking it to see if there is any play. There shouldn’t be any lateral movement at all. If there is, you will probably have to get hauled to replace it. A spare should be part of your inventory. If you keep the old one, you can use it as a tool to force the bad one out. (All in the Same Boat, p. 150)

- ….gear that are[is] all too often ignored are the cutlass bearing…The cutlass bearing is a bronze tube with a grooved rubber liner that fits inside the fiberglass tube through which the prop shaft exists the hull. Replacing it is relatively simple. While the shaft is out, pound out the cutlass bearing with a hammer using a section of wooden dowel of the right diameter. There may be a few set screws or allen nuts to remove first, but that’s it. (Upgrading the Cruising Sailboat, p. 150)

- A cutlass bearing is nothing more than a short length of naval brass or composite tubing with a splined hard-rubber liner. The rubber supports the propeller shaft where it exits the hull, and channels allow water into the bearing to serve as a lubricant and to wash out sand and other abrasives. The bearing’s inner diameter matches the diameter of the shaft, and the outer diameter is a snug fit for the stern tube or bearing housing in the strut. A Cutlass bearing can last 10 years or longer when the shaft is properly aligned. No maintenance can be done on a Cutlass bearing; either is is OK or you replace it. (This Old Boat, p. 175)

- Compared to removal, replacement is a piece of cake. First lubricate the new bearing with soap – never grease – and slip it onto the shaft to confirm the fit. It should rotate easily. Lightly coat the outside of the shell, this time with a thin grease, and try to slide the bearing into the house. A few love taps with the bearing protected from the hammer by a wood block are OK, but if it doesn’t go easily, don’t just hit it harder or you’ll distort it. Put it in a freezer or pack it in ice for a few hours, then try again. The cold should contract the metal case enough to make the difference….You may also find Cutless bearings around the rudder stick where it exists the hull. These bearings are removed and replaced in the same manner. (This Old Boat, p. 175)

- DIY Removal of Cutlass Bearing

- Removal of cutlass bearing of Triton boats

- Replacing the Cutlass Bearing

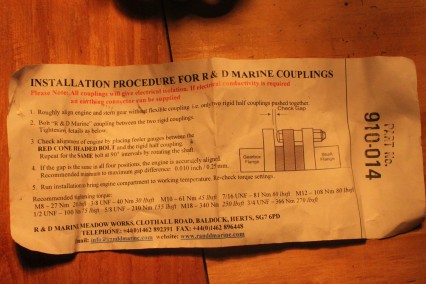

Flexible Coupling

- One might consider fitting a flexible synthetic coupling between the engine and shaft…this coupling reduces vibration and noise, and more importantly, prevents stray electrical currents in the water from causing corrosion in the engine. Most new diesels are fitted with sacrificial zincs. but it’s nice knowing you have double security. (Upgrading the Cruising Sailboat, p. 147)

- In most cases of shaft loss, the propeller shaft is held in its coupling with set screws that work loose. If this (common) method of attachment is used, it is essential to ensure that the set screws seat in a good-sized dimple in the propeller shaft, and that after being done up tightly, they are locked off so that they cannot possibly vibrate loose. The most effective method of locking the screws is to drill a small hole through each screwhead and then tied them together with stainless steel or Monel locking wire. However, I prefer to drill right through the coupling and shaft, and add a through-bolt held in place with a Nylok nut. This method is almost foolproof…Coupling bolts need to be locked off (with lock washers, Nylok nuts, or locking wire). (Cruising Handbook, p. 203)

Propeller

- Engine performance is only as good as the propeller. The first consideration should be to deal with the mistmatch that can occur between efficient engine speed and efficient propeller speed. Most engines for cruising boats run efficiently in the 1800 – 3000 rpm range, while propeller tip speed and blade areas work best at about ½ those speeds. The solution to this problem is to install a reduction gear on the engine to cut the shaft speed. But…the compromise is that reducing shaft speed (and, with it, propeller rpm’s) means that a larger propeller must be installed so that thrust is not lost, and a larger propeller adds drag and reduces sailing speed. (Desirable and Undesirable Characteristics of Offshore Yachts, p. 238)

- If the yacht has a full-length keel with the propeller in an aperture, a good compromise between good thrust and low drag is to use a two-bladed solid, nonfolding or nonfeathering propeller, whose blades can be aligned with the keel when the boat is under sail, (Desirable and Undesirable Characteristics of Offshore Yachts, p. 238)

- Cruising people have benefited by the development of the low-drag folding or feathering propellers for racing yachts, and modern folding and feathering propellers are nearly as efficient as solid ones. However, some owners elect to have both kinds of propellers – the feathering or folding type to be installed before a cruise that will made mainly under sail, and a solid type for a long passage that will require a lot of powering. If the two propellers have matched machining, they can be changed in a quiet harbor without the need of…haulout. (Desirable and Undesirable Characteristics of Offshore Yachts, p. 238 – 9)

- Choosing the right propeller for a given boat and engine makes all the difference in performance and fuel efficiency. There are so many variables affecting correct pitch and size that scientific selection is difficult for the average person. Propeller sizes are given in pair of numbers, such as 13×9 or 12×8. The first number refers to the diameter of the blades in inches. The second refers to the pitch, or angle of the blades and is the number of inches the prop theoretically should move forward with one revolution. The greater the pitch, the bigger the “bite” the prop takes. (Upgrading the Cruising Sailboat, p. 148)

- Many engines have reduction gears to the propeller shaft. A 2:1 reduction gear means that the engine is alays turning twice as fast as the prop shaft. An engine with 2:1 reduction gear would use a larger prop than one with direct drive. The smaller size for the direct drive is necessary because through the prop turns faster, there is less torque to keep it turning under load. (Upgrading the Cruising Sailboat, p. 148)

- …fixed two blade props locked in the vertical position offer about 15 – 20% more resistance than feathering two-blade props. While this evidence is compelling sometimes these props don’t like to open correctly. The cruising sailor who wishes to avoid as many repairs as possible may find the fixed blade prop the wisest choice. For the cruising sailor, it is less a decision and more a matter of personal inclination whether to power to windward or accept that Neptune delivers and do the best under sail alone. To effectively motorsail in heavy seas, a large propeller with high pitch coupled with reduction gear is the best combination. But the increased drag acts a price in sailing performance. (Upgrading the Cruising Sailboat, p. 148 – 9)

- There is a choice to be made between two and three bladed props as well. The two bladed prop will give about 5 – 10% more speed than the three-bladed prop under sail, though the latter is slightly more fuel efficient under power and vibrates less. While converting from three blades to two, it is unusual to increase the diameter. (Upgrading the Cruising Sailboat, p. 149)

- Variable pitch propellers have much to recommend them in that the pitch can be adjust for different speeds and sea conditions, depending on the torque requied.

- At full speed the tach should reach the engine’s rated maximum rpm. If the engine fails to achieve the rated rpm, the prop may be too large or the pitch too great.

- …the folding propellers, especially the two-bladed type, offer the least drag under sail but have the worst performance under power, especially when in reverse. The feathering propellers (e.g., Max Prop, Martec, and Luke) create a little more drag under sail, but perform about as well as a fixed bladed propeller in forward, and almost always perform considerably better than the fixed propeller in reverse….my only comment is that at some point, the propeller may get damaged….Some of the feathering propellers require more disassembly to get on and off that others. Some also require the propeller shaft to be modified (which makes it difficult to retrofit a fixed-blade propeller); others fit onto a standard propeller shaft. (Cruising Handbook, p. 202)

- An MIT velocity prediciton program suggests that the average impact of a three-blade prop compared to no prop is about 5% of boat speed, with the impact being greater in light air and less as sails develop sufficient power to overcome additional drag. Rare is the cruiser who does not hit the start button when boat speed drops to 2 knots. (This Old Boat, p. 138)

- …I tend to come down on the side of less complexity. Fixed props are simple and foolproof. Feathering and folding props are neither, so be sure the benefit for you will justify the added complexity. (This Old Boat, p. 174)

Propeller Shaft

- The distance between the engine-half coupling and the end of the cutlass bearing in the stern should be measured. Most prop shops use dimensions calculated to the SET or small end of taper.

- A measure of security [if a shaft were to fall off] can be provided by putting a host clamp around the propeller shaft just forward of the shaft seal. If the shaft comes loose, the hose clamp keeps the shaft in the boat. However, with certain high speed shafts, the clamp may cause sufficient imbalance to create vibration. It may be possible to remedy this by using two hose clamps with counter-posed screws. If not,t he clamps will have to be left off. (Cruising Handbook, p. 203)

- The installation manual will recommend shaft diameter, but the rule of thumb is 1/14 of prop diameter. This assumes bronze or stainless steel. An Aquamet shaft can be up to 20% smaller….be sure to buy a cutlass bearing to fit it, but with the shell diameter of your existing bearing. Otherwise you will have to replace the stern tube, a bigger job than you might want to take on.

Stuffing Box & Shaft Seal

- Conventional packing depends on water to lubricate it, and if you have the box well adjusted, it drips only when the shaft is turning, but there is a way for sailors to make a conventional packing dripless (This Old Boat, p. 164)

- Replace the stuffing box with a mechanical seal. However, stuffing boxes lose their seal graudually and never catastrophically. Shaft seal failure is more likely to be sudden and dramatic. Be sure to learn what care your particular shaft seal requires and see that it gets it. (This Old Boat, p. 164 – 5)

- Face seals operate on the principle of a sealing ring rotating against a machined flange, one turning with the shaft, the other held stationary by clamping it to the stern tube. The two are pressed together by some type of “spring” pressure, usually a rubber bellows but sometimes water pressure. Unvented face seals need to be “burped” after launch by compressing the bellows at the top until water pours out. Otherwise trapped air will cause the seal to run dry, which it is not designed to do. Burping the seal each time you service is probably not a bad idea. Bellows “set” combined with weakening engine mounts can allow enough forward shaft movement when the prop is engaged to open a gap in a face seal. Poor engine alignment or excessive drivetrain vibration will stress any mechanical shaft seal. (This Old Boat, p. 164 – 5)

- Lip seals are simply an adaption of a common oil seal. They are installed in a bearing housing that clamps inside the shaft tube hose. The thin rubber lip of the seal runs against the surface of the shaft, usually held in contact with an internal elastic or spring collar. Lip seals are nearly always plumbed for lubrication by either water injection or gravity-fed oil from a reservoir mounted above the seal. (This Old Boat, p. 164 – 5)

- Shaft seals are not supposed to require any maintenance, but don’t believe it. All of them use hose clamps that need to be checked at least annually, some face seal designs depend on setscrews to secure half of the seal to the shaft. Make sure the set screws are not tightened against the hard, smooth surface of the shaft. The shaft should have been dimpled with a drill when the seal was installed. To do this, buy a new cobalt bit smaller than the hole, shrink an inch of electrical shrink tubing onto the bit to avoid damaging the threads, and dimple the shaft through the threaded hoe. Turn the shaft to roll the hole down and blow or flush out the drill shavings with an ear syringe. Coast the setcrew with Loctite and reinstall it. Give the remaining setscrews the same treatment, one at a time. For belt-and-suspenders security, tighten a hose clamp or a new zinc collar around the shaft hard against the seal collar. (This Old Boat, p. 164 – 5)

- …I am a fan of the “drip-free” mechanical seals, of which of my two favorites are the PSS and the John Crane (Halyard) seal. Given a well-aligned engine, they really are drip-free…If a mechanical seal is fitted and the boat is hauled, it is important to remember to pull back the seal until water squires into the boat when the boat is re-launced. If the seal is not lubricated in this way, it may burn up – which is when you discover the real drawback of these seals: the propeller shaft has to be withdrawn from its coupling to install a new seal. (Cruising Handbook, p. 203)

- I have had dripless or PSS seals on many boats as well as traditional stuffing boxes. I worked on a 55 foot sport fisher that had over 5k hours on two PSS seals with zero issues. My buddy Jerry owns a 100+ foot “yacht” (how the other half lives) and it has two huge 16 cyl Cats and two PSS shaft seals. Boat has perhaps 70k nm on her and not a single issue. The one on our own boat went for 2782 hours before I replaced the bellows. I shipped the bellows to PSS and they tested it within like new specs at 6 years old and 2782 hours. Lots of reputable builders such as Sabre, Valiant, Hinckley, Little Harbor, Pacific Seacraft, Swan and the USCG use them too. Both types work and as Tim said with new packings, such as Johnson Duramax Ultra X, Gore GFO or Western Pacific Trading GTU the traditional boxes can be made to drip very, very minimally. (http://www.plasticclassicforum.com/forum/)

Comment Form