Hull #352 – Steppin Out

Image Gallery

Quick Facts

- Model: Dinette version

- Year Built: 1975

- Hull #: 352 (BTY273520175)

- Vessel Name: Steppin Out

- Owner Name: Jaime Corvalan Kahler

- E-mail: jaime.ck@icloud.com

- Hailing Port: Marina Austral, Aysén, Chile, Sudamérica

Sailboat History

January 2021 – Jaime Corvalán purchases Steppin Out from previous owner. The boat is kept in Marina Austral (www.marinaaustral.com) in Chile. Here’s an image of the boat in the marina:

Steppin Out in Marina Austral, Chile.

July 21, 2015 – First I (Daniel Bravo) have to introduce my boat and make clear that talking about her is like talking about my child. Being my only possession, my home, my companion of journeys and the material expression of a philosophy of life I do feel somewhat proud of talking on her behalf.

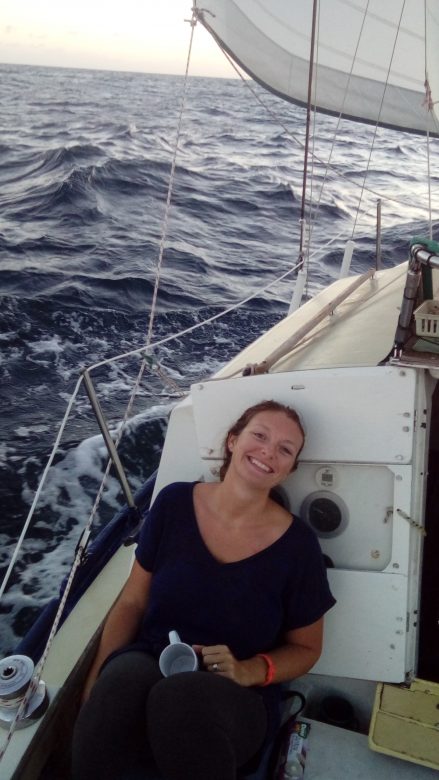

My girlfriend (now wife), Emily, my boat, Steppin out, and me, We form an itinerant family and I love them both deeply.

I found Steppin Out on the internet looking for a new partner after sinking my previous boat on a rather awful (and somewhat stupid) accident in Uruguay. I got it for $4000 in Melbourne Florida, from the hands of a certain individual whose only merit had been behaving towards “steppin” with total lack of care and technical rigour. The boat was structurally sound, but it was basically a floating trash can.

After solving the legal mess that came with the boat and getting the title finally under my name, a long process of modifications started, the most important being the outside lamination of the toe rail to stop the generous leaks in the hull and deck joint. Then I got rid of the of the atomic 4 inboard, trading it in for an outboard lifting bracket. Getting the engine out was like extracting a smelly, noisy and useless tumor from inside Steppin.

Then came the moment to design and mount the wind vane self steering. Based on a further development of Joshua’s model (Moitessier’s boat), I designed a sturdy and reliable system, not the most efficient, but probably one of the strongest possible solutions, based on a pivoting steel bar that connects a big wind vane with a small oscillating rudder. Steppin was then not just a fiberglass machine but a living being able to communicate and react by herself to the wind.

After the basic safety additions -including a life raft and epirb- we sailed Steppin to Isla Mujeres México, where I stayed for two years working as a charter captain to recover my economic buoyancy.

The only previous relevant journey that I knew of the boat was made by the previous owner from Florida to the Bahamas, so there was no big evidence of real offshore skills on the boat, although a boat that was almost 40 years old and was still floating, probably had proved herself seaworthy many times.

On the journey to Mexico the boat proved to be both pretty slow (no one is perfect!) and remarkably strong, the latter being the most important feature to me and the reason to buy this particular design. After facing a couple of squalls I immediately admired the feeling of reliability.

During the two years in Mexico further modifications followed, most importantly, the change of the rigging from sloop to cutter and the duplication of the cap shrouds and backstay.

Once my economic capacity was reestablished and the boat was ready, came the time to leave. I met my girlfriend Emily around that time and, attracted probably by the spacious interior, she decided to sail with me on Steppin. We have savings for some two years and after sailing up all the east coast of the USA (wonderful journey, full of history and good friends), we headed from New York to the Azores.

The journey across the Atlantic was exceptionally good basically because we chose the right weather window and were lucky enough to have only one force 7 that lasted two days and was sailed under storm jib on the babystay, while we were comfortably watching movies and reading inside.

After 24 days of sailing at an average of 3.5 knots, we arrived about a month ago to the Azores and right now I’m writing on a nice long chair on a beach in the island of Graciosa, after visiting Flores and Faial.

Steppin is floating in front of us, always ready to lift anchor and sail far.

Owner Comments

January, 2022 – My name is Jaime Corvalán, the new owner of Bristol 27 # 352 (“Steppin Out”). Before, Steppin Out belonged to Daniel Bravo, from Chile. I have the sailboat in a marina since January 2021 in southern Chile, specifically in Puerto Aguirre, Aysén, Chile. It makes me happy to keep in touch with you and the Bristol 27 community.

[Here’s some photos sent by Jaime:]

Steppin Out viewed from club house of Marina Austral.

Marina Austral setting, with Bristol 27 safely docked.

Bristol 27 Steppin out sailing near glaciers in Chile.

June, 2018 – Rounding Cape Horn

“Most quests are not as broad or as long as Slocum’s and do not need to be. Thoreau found more in a Massachusetts pond than some find in a lifetime at sea”

Charles Borden

Hi guys!! It’s been long since I’ve written something worth reading. I’m not quite sure this is going to be worth reading, but here we go… a brief story of the trip to Patagonia.

First of all, sailing Cape Horn is like (and its always been compared to) climbing Mount Everest, it’s the only expedition in sailing that reaches one specific point, has a huge load of history associated with it and represents a challenge where many people fail or give up one way or another. Crossing an ocean is similar, but, in most cases, technically a lot easier, unless you choose some exotic route.

Still, Cape Horn is just one more “challenge” to take, and someone could ask “Why not Antarctica?”, or “Why not sail around the globe at high latitudes?” or “Why not be the first one to cross the Atlantic upwind in a ceramic bathtub?” In my personal case, at least, there is no point in asking any of this: I’m doing it simply because I felt it, because it is a long desired pilgrimage done in an almost religious way to the maximum temple of my faith: The ocean. Furthermore, if I’m doing it on a 27 foot boat with a 10 horse power engine is because of one simple and mundane reason: It’s the (only) boat I have.

Despite all that, there might be one merit to this attempt: it was made with very little resources, so little that even a third world sailor (like me…) could consider going to a place that sees usually only first world flags and or, very rich South Americans in very fancy yachts. So, I think there is something to be said for a project based on a US$4000 boat with an initial budget (for 5 months) of some 1500US$. It’s not easy, and still it’s not cheap, but compared to the yachts that usually sail the area, (between 5 to 40 times more expensive) and, say, climb Mount Everest with a cost of some 40,000 bucks, this looks a lot like a working class type of challenge. Maybe, just maybe, another guy reading this somewhere will see a way through it.

Steppin’ Out is a well-used and well proven Bristol 27, the usual hard core, old school offshore sailboat: Cheap, sturdy as hell, reliable as an ox and slow, very slow. She has crossed the Atlantic twice in my hands and by now I have modified every weak point and every possible trouble source, the list of small modifications is long and there is no point on going through it, but it can be assumed that the mast won’t likely fall, the hull probably won’t break and the keel and rudder tend to stay where they should, as opposed to some distressing newer boat tendencies.

The boat was left in Piriapolis, Uruguay for six months, during which I went to Chile to work and make money for this adventure, upon my return my friend Mane and I found the boat in good shape, still standing right side up in the concrete compound of the port. Looking a little dirty and sun dried, but otherwise ok, we made a very quick (and sloppy) job painting the hull without even sanding it, and putting the acrylic windows on the cabin that I had made before leaving the boat the previous autumn. Without spending any extra time in the port, we went to the water and promptly out to sea.

The boat could have received, as usual, a little more TLC, but you´ll always find good reasons to postpone a journey, so if the wind blows, you set sail and slowly deal with your fears as you become part of the offshore landscape.

The coast of Argentina is governed mainly by two phenomena: the depressions parading on the south of the planet and the katabatic effect of the westerly winds coming from the pacific. As the wind crashes with the Andean range, all its humidity is left on the Chilean side, the wind rises to high altitudes, gets cold and dry and, on the other side, having gained density, falls like a rolling stone down the hills of the high mountains, sweeps the pampa and arrives to the coasts, always blowing like hell, always from the west or south west and always very, very dry.

Windy anchorage in Argentina.

Our sailing strategy was very simple: stay close to the shore and enjoy the wind without fetch to allow for a sea state to develop. It’s an easy game, if you see a “bomb” coming from the west, you run for your life to the shore and stay sailing there at perfect sight of the coast, some 5 to 10 miles offshore and either anchor pretty much wherever you want, or keep sailing along the shore on a very fast and frenetic close reach.

Like most people, we planned to stop in Mar del Plata and jump from there to the rest of the of the Argentinian coast, but a satellite message from Em made us change our plans: Other sailors had reported very strict checks from the Argentinian navy on all the sailing boats passing by: they were requesting absurd gear items like enough flares to make a firework show, a bell (yes, a bloody bell) and an axe, fire extinguishers, harnesses, life raft, etc, etc. Our life raft, needless to say, was expired (not much) we had just one not-expired flare and definitely no bell, axe or any other weird and unlikely safety item. Some boats had to pay up to 2000 bucks in fines and gear to be free of the Argentinians’ claws. Obviously that would have been the end of our trip so we kept sailing towards Quequen, widely regarded as a more welcoming place.

Quequen was, indeed, absolutely awesome. The “Vito Dumas” sailing club had saved the image and spirit of the Argentinian sailor, who, oddly enough, is a rather mis-valued character in Argentina, despite being clearly right up the hall with Slocum, Moitessier or Knox Johnston. At the Club they have an understanding of sailing as poetry, this very rare occurrence of a club that sees the redeeming relevance that the ocean and the wind have for a person’s soul.

We fit right in and, although we only stayed there for three days, that was the perfect spiritual beginning to our quest.

Steppin Out crew with the Vito Dumas sailing association.

In Quequen we found very easy going maritime authorities that were obviously used to dealing with the offshore inspiration of the local club and were not surprised or annoyed by the presence of cruisers in Argentinian waters. Everything went smoothly and we had no need to show our recently “brought up to date” certificate of the life raft. We obviously enjoyed quite a lot of stress in the presence of the armed forces, as is usually the case, until we were freed with all papers and checks in order.

After leaving Quequen, there is a feeling of uncomfortable fear, the ports and bays towards the south have rather ill fame: San Blas: windy, with loads of current, easy to drag the anchor, three members of Vito Dumas Club had died on the surrounding coasts… Puerto Madryn: not really a port, just a massive bay without any wind protection, loads of current at the entrance and exposed, barren, low surrounding lands, all of it swept by violent winds, Caleta Hornos: good, the only good one. Puerto Deseado, easy entrance, bad anchorage, unavoidable as it is the only real port before the extreme south, but, by all descriptions, not a very desirable place, with the inhabited shore on the lee side of a very windy and wide river. Then, further south, Lemare Strait, where even Marcel Bardieux managed to capsize his boat… incidentally bigger than mine…Let the fun begin!

The first technical sailing challenge is faced right south of Peninsula Valdez, under the premise of “anything with less than 50 knots is a good weather window”, we managed to skip Bahia San Blas and Madryn. Then the problem was that all our strategy was based on staying ridiculously close to the shore, and as it turns out, Peninsula Valdez is big, and it ends pretty far offshore and the direction towards the shore is a straight west bound course, right against the prevailings. But… according to the forecast, we had 10 hours of north before the next westerly festival, this is when the always available satellite forecast makes all the difference, we had 10 hours to make 60 miles to the west, had we not known of the arrival of the Westerlies we might have taken it easy, we would have sailed relaxed towards the west. In our case, we turned on the engine, hoisted as much sail as we could, disconnected the self-steering and made 6 knots average on a wild reach right towards the shore, no questions asked, all steam full ahead.

Towards the end of our wonderful north wind window we had the shore in sight and were ready to take whatever could come from the west, we kept sailing south and stopped on Bahia Jensen, a wide and open bay that provides shelter only from the westerly winds. We positioned ourselves very close to the shore with the wide open seas on our back, in case we dragged, and it blew… a lot. We spent a very relaxed Christmas there, knowing that, in the worst case scenario, we would wake up floating some miles away from the shore in which case either a hard upwind leg towards safety, or a Jordan Drogue would have been in order.

Caleta Hornos,on the argentinian coast, is an excellent anchorage, described by every sailor as an earthly paradise, but as it would happen many times, we were sailing a wonderful reach south bound and the forecast was excellent to continue. As some old sailor in this area told me, “here, if there is a good window, you sail, you don’t stop”. So off we went, kept moving south across golfo San Jorge, where the wind gets enough fetch to become dangerous if things get ugly.

We had to make it right at the end of the weather window to enter into Puerto Deseado… and we didn’t quite make it, the wind, always from the west was systematically gaining strength and when we finally made it to the entrance, it was plainly obvious that the engine was absolutely unable to push us against the wind (not very surprising) and tacking in the narrow entrance was a bad idea at best. So there we stayed, prepared a nice heaving-to condition and dispose ourselves to wait, coming and going in front of the small city, blown by the eternal Westerlies. 12 hours later, at dawn, the weather decided to give us a respite, even before light the wind had calmed and the seas, being 2 miles away from shore, were almost immediately calmed. That was our chance and we made the best of it, at midmorning we were anchored on the only place that could offer any protection in a bay that could only be described as very bad. The proverbial instability of the southern weather had already started and the weather was a series of drastic changes of heavenly mood, with dark clouds, strong gusts or calms parading endlessly. And Steppin’ was anchored with a lee shore some 20 meters on her stern; two tandem anchors in the water were the only life line dividing existence from destruction. Needless to say, I wasn’t at all relaxed in that port and during our wait for weather, many times Mane went to town to get us supplies while I sat either on the boat or on the shore right in front of her, trying to recognize the start of the movement that might very quickly end on the rocks. Beside me there was a couple in a camper van, a big-ish and comfortable thing, the land equivalent to a nice sailing boat, but sitting, in its case, over 4 tires that would require a veritable hurricane to make that thing “drag”: Oh, lucky land roamers! Steppin’ kept on rocking while facing the eternal wind.

At this point must be observed that Mane’s, and all my crew’s resilience is nothing short of admirable, in the most traditional personification of a grouchy old seaman (I’m too young for that…), onboard I usually behave in a rather insufrable and pesimistic way, and my sailing mates had to survive not only the hardships of the sea, but the dark fantasies of my most unbearable mind, that had already broken the mast on a violent pampero off the coast of argentina, dragged against the shore in an exposed anchorage, capsized the boat in the waves of Strait of Lemaire or burnt the engine in any of the long southern canals. This less than ejoyable characteristic has the dubious merit of keeping my expectations low and the mood always ready for disaster, but it’s mainly a way of protecting myself from the dissapointment of an unexpected problem. A good captain, though, should keep the worst scenario in his head and the optimism in his mouth… Unfortunately that’s not me, my head and mouth have been way too well connected for my own good along the years. Despite that, and not because of my own merit, we always had very good relationships and mood onboard, esential ingredient to the succes of this mission.

We left Deseado with a forecast that was rather confusing, unstable, full of wind changes, but more than anything, very calm. So far it hadn’t been really necessary, but according to all opinions, at some point the engine was bound to claim a rather relevant role in this journey so we filled up with diesel and three extra jerry cans, aware of the possibility that this next leg was the start of many hours of diesel burning on the “iron genoa”.

A calm, at these latitudes is a good thing, a very, very good thing. One thing you know for sure is that, once it is gone, the calm won’t be followed by a nice 15 to 20 knot breeze, but will be followed by something described in most forecasts with blood-red tones. So, yes, me, the same guy who sailed from Mexico to the Med and England with a 5 hp outboard without ever really using it, here was very much ready to press the button and get those beautiful 3 knots that the 1GM10 was able to provide.

The whole coast of Argentina has a very distinctive and rather strong tidal current, every 6 or so hours, the whole ocean that lays in front of this coast moves north and south, it’s a massive amount of water and it comes from the south, where the tip of Tierra del Fuego and Isla de los Estados forms a natural barrier to this massive movement, this barrier, has, nonetheless, a gap. This gap is called Lemaire Strait to honour a certain gentleman who had the courage to sail these waters and the ignorance of not recognizing the skilled sailing tricks of the natives, the names they gave to the places and the observations based on centuries of water passages that they possessed.

All the water flow can pass either outside of Isla de los Estados or in between this island and Tierra del Fuego, where this current swept strait lies. The passage through this area has to be very carefully timed with tide and weather, and the fact that we arrived there 6 hours before a perfect weather and tide window can only be considered a present from the ocean gods. Few hours after reaching Bahia Thettis, on the easternmost tip of Tierra del Fuego, Steppin’ was flying south with a very rare easterly wind and the strong current pushing hard. Right south of it, nonetheless, we were greeted by the southern ocean with its ever flowing east bound current. “It’ll turn on the next tide,” we thought: Mistake. It gains or loses strength, but south of Tierra del Fuego the river always flows east. Back to full steam, engine, hand steering, several hours at one or two knots, despite the fact that the wind was pushing us nicely and the engine was doing its bit…Quite scary, really: The easterly wind was not going to last more than 12 hours, and if you don’t make it to Picton or, at least, Puerto Español before the Westerlies arrive, you’ll float very far and will be forced to grab one of the anchorages south of Isla de los Estados.

Some people go to Falklands and then they sail back, against wind and current, this is commonly done and maybe Steppin’ would be able to do it, but I seriously doubt it and, anyways, I definitely did not want to try it, so we kept pushing, hoping to make Picton soon enough.

And we made it! Steppin’ Out arrived to the island of Picton and was geographically north of the Cape, with prevailing Westerlies and with the (dubious) protection of the Nassau Bay (which can get pretty nasty), this journey could be done easily, provided the forecast was peaceful enough.

Many people ask, “Well, how is sailing the cape?” I guess the answer is, “Like sailing around any other small island in the world.” Because once you have broken your nerves all along the Argentinian coast, feared for any possible failure, mistake, change of tide, anchor drag, ripped sail at the wrong moment, etc. sailing around The Horn is just one more step, despite all that, the penalty for those who take this without the necessary seriousness is death, and that cannot be forgotten.

This is an easy step, if you have satellite forecast, like we had, without that, approaching that area of the ocean, at least on a boat like ours would be, in my honest opinion, close to suicidal.

We were even feeling too sure of ourselves, Mane and I were talking about the “right way” to sail The Horn, maybe we should agree to not use the engine during that short passage, maybe we should pass from east to west, or west to east… we were discussing as if our desires, our stupid and arrogant human pretensions, our wish to build a meaningful moment, our understanding of what was “correct” or “cheating”, was of any relevance to the ocean. We were approaching from the north, sailing straight south towards Martial Bay, our last stop before The Horn, and as we turned west, south of Freycinet Island, all our pretensions were erased, all our discussions were put in their place: A very strong series of williwaws (sudden, violent gusts) developed inside the bay. The wind outside was strong, but inside was very close to unmanageable, we found ourselves very quickly under storm canvas, engine pushing and Steppin’ still being carried towards the uncomfortably close lee shore. After a couple of hours of stressful struggle, we made it into the bay and everything seemed peaceful again, but we had gotten the answer that we were waiting for: here, it is the ocean who decides how you sail, and to willingly spare any of the available resources is foolish at best.

The next day we had an excellent sail around The Horn, we passed east to west and at the end of the day we made it back to Martial Bay.

It’s, really, not The Horn, or this ocean, or that bay, the personal challenge is an intimate experience, whose relevance only one can assess. Many people have made equivalent journeys to this one on Steppin’ Out, even one guy called Jarle Ahoy made it to Antarctica on an Albin Vega when he was very young, some guys have crossed The Cape in Hobie Cats and so on. To me, at 32, I had finally gathered the necessary resources, the experience, the time to accomplish something that I had dreamt of since I was a kid.

After almost 8 years specifically trying to make it, I had finally crossed in front of The Horn. Who is to say what is harder and what is not? What is a challenge worth accomplishing and what is an everyday trip? I sunk a boat, crossed the Atlantic five times before arriving to this moment, put all the savings and material capacity of my whole life into this, the same way that someone maybe put all that effort to cross the Atlantic, the Bay of Biscay or maybe just the Solent or the narrow sea between Florida and The Bahamas… the weight of the experience is within each one, it is not The Cape, nor is it one particular bay or ocean, it is the relevance of having a dream and fulfilling it, no matter how hard, how long or short, how far or how near. The Horn is, I’ve always thought, a temple, maybe it is the temple, the monument, erected by the gods to our capacity to dream.

Captain Bravo at Cabo de Hornos (Cape Horn).

The next morning we sailed north from Caleta Martial to Puerto Toro, Harberton in Argentina and finally, Williams in Chile, where a very sad episode in this journey was about to start.

As soon as we set foot in Williams we were informed of two things: first from customs: “You have 15 days to pay 35% of the price of your boat in taxes, or the boat will be confiscated at the end of this dead line”, then it was the navy: “you sailed Cape Horn coming from Argentina without authorization from the Chilean government and without formally entering the country first, the navy requires you to have an interview with the port captain”.

The general disposition towards Chilean sailors has never been good in Chile, so I was more or less prepared to have some minor difficulties of undefined kind, but the 15 days before the confiscation of my boat was something that I was really not expecting.

At the moment the requirement from customs sounded, to me, extremely unfair and I still feel that way, but as it turns out, at least England and Australia have the same disposition, if you are a national of the country you are forced to pay the importation taxes of your boat immediately. Once I finished fighting against the idea and accepted the unavoidability of it, there were two missions: first, get a very low quotation for the boat and, second, find a job to generate money while I was sorting out the legal issues. As it turns out, the quotation had to be made by a naval architect, so that was easy enough, I cannot sign my own quotation, but any of my friends can, the second mission was soon to be sorted too, and very soon I was sanding and painting the hull of the 37 footer belonging to an instructor of the local sailing school.

One month later I had paid the 1000 bucks for the importation of the boat and had made some 600 bucks from my recently acquired job, the boat was free again to sail and I had to borrow money from a friend to be paid within the next months, or basically, as soon as I was able to.

My co-skipper Mane had left with the hopes of coming back, but his personal business was in a worse state than expected so he asked me to leave the crew permanently and offered to pay flight tickets for whoever could come and take his position. Another friend, Nacho, also a naval architect and sailor came to join the second part of the journey, and as soon as he was there, with one month’s delay from the original plan, we sailed towards the north.

After a month in Williams, I had made a decent number of good friends, king crab fishermen, the remarkable welder of the comercial port, and all the working team of the sailing school of Williams. They had, right at the moment when we were leaving, a big amount of flavoured milk and cakes that had expired a couple of days ago, they couldn’t give those to the kids of the sailing school, but for a rat-eater broken sailor this was pure gold, they gave us some 100 individual boxes of milk and cakes. A month later they were still our main source of energy while sailing, not to mention one of the tastiest things on our rather simple menu, otherwise composed mainly of rice, pasta and instant mashed potato.

Donated food is a big help.

I thought this part of the journey was going to be easier, less risky, with plenty of anchorages in the canals, nice landscapes and, generally, less exhausting sailing. Well, once more I was very, very wrong.

The prevailing winds in the whole area from Williams to Golfo de Penas is either west or north winds. There are no side winds in the canals, the wind will always align itself with the canal, even if it comes almost sideways to it. Furthermore, once you’ve passed towards the west side of the Andean range, you promptly find out where all the humidity that was missing on the Argentinian side was left. The wet air of the whole Pacific Ocean condensates and falls in endless showers as soon as you’ve crossed over to “this side”.

You can all more or less imagine the scene: 600 miles of canals from Williams to Golfo de Penas with eternal rain and contrary winds. The Argentinian side, accompanied with a well thought strategy and technically proper sailing, was quite acceptable, almost easy sailing. But now there was no way around it: everyday was an eternal series of tacks, hand steering under the rain and cold, always in the cockpit, making between 15 to 30 miles per day…: A wet and exhausting task, without technical sophistication or glamour, just hard core, old school, slow progress.

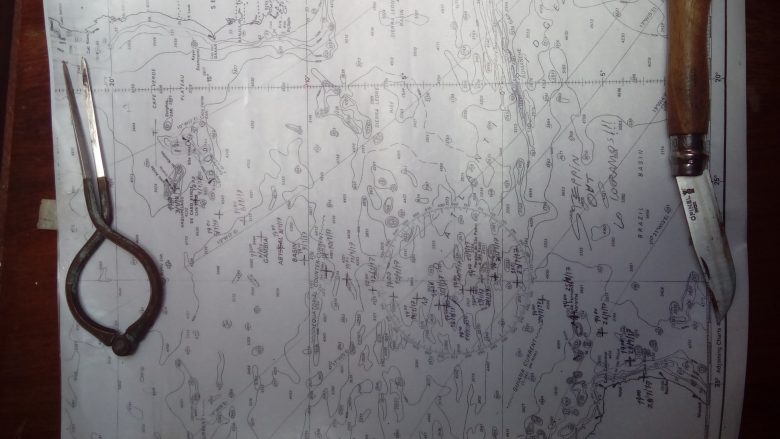

Nacho, my new partner in the adventure, had a rough initiation and the very first day, a big calm and easy motoring day ended up turning into a nasty blow from the west which forced us to look for shelter on one of the many anchorages that make sailing in this area possible. The following month followed the same logic: early rising, sailing for 10 to 12 hours, anchoring after few miles of progress and going to a wet bed with wet clothes. Without heating, drying anything was impossible and the condensation inside the boat, kept closed at night to keep in some warmth, had arrived to all the places where the rain and sea water couldn’t reach. When we arrived to the Strait of Magellan our nerves were very much on edge: once you leave canal Acwalisman, you look at the chart and there are 100 miles of northwest aligned canals. I asked my weather router, a good friend who was always available to give advice, and he said “at least for the next ten days that I can see on all the forecast, there is nothing but strong north west winds”. 100 miles doesn’t sound like much, even Steppin’ has made 100 miles in 24 hours… It took us two weeks. Two painful, long, upwind weeks.

Making it through two weeks of grueling sailing.

We were almost done with Magellan, arrived finally to an anchorage right south of Cabo Tamar, the legendary rock that protrudes towards the west and blocks the way to the north, where easier channels offer some hope.

And there we ran out of luck, found ourselves in Caleta Uriarte when the awful weather started, we had had strong winds for most of the previous weeks, but the gusts that we saw there, some of those days and nights on the cold and wet loneliness of Isla Desolacion were deadly, we had four lines to shore. All the available ropes on board were attached one to the others and the boat was secure enough with 400 meters of rope, but still some of the passing gusts heeled her right to the side of the cabin, temporarily submerging the salon windows, sleeping was hard, keeping your mind off of the fear of having one rope break was almost impossible.

6 long days we were waiting for a chance to sail north, 6 days inside the boat, while outside the wind and rain were hauling tirelessly on the rigging and the threes. After those 6 days we were able to leave the caleta and cross to Canal Smith. Slocum left the canals right there, he sailed to the open seas and I can very well understand why, but I guess I still deemed it less dangerous to keep tacking upwind over the risk of being pushed towards the rocky Chilean coast by a violent westerly in open seas.

And things improved… not immediately, but once we left Magellan we had some days without rain, some days with no wind at all where we could motor for long and peaceful hours, there was one day, I remember it very well, one day that we sailed and we enjoyed it, we turned the engine off (even tacking upwind we always had the engine helping), there was a decent breeze from the south, it was sunny, we put music from Silvio Rodriguez and looked at the sun, the mountains, the shiny water and we felt alive, we were still very, very far from our destination, still south of Eden, but it felt sooo good, the light of the sun fell on us like a rain of hope and fulfilment. We had left the worst of it south, that day, when we arrived to our intended anchorage, we were almost sad to drop the anchor and stop, we were not wet, not exhausted, not worried. I remember we had that one beautiful day.

One of the better sailing days.

Eden is a small town, not even a town, just a bunch of houses inhabited by 80 people; it’s the only human population between Golfo de Penas and Eden, on this side of the mountains (Natales is on the other side, hence very far from the route). Arriving there felt wonderful, Nacho was to depart from there back home and another friend, Cristobal, would join me. It had taken us a month and a half to sail from Williams and we had been wet and tired almost all the time. Nacho was proud, happy to leave, but happier for what we had achieved. North of Eden everything is easier simply because there are towns more often to solve problems or resupply.

Cristobal arrived and we had two amazing days of good progress on our way to Canal Mesier (80 miles in two days!!), at the mouth of Golfo de Penas. We shared the journey there with the yacht “Otra Vida”. While the journey with Nacho was lonely and hard, with Cristobal we were actually having fun and easy days, good company, laughs and dinners in the salon of “Otra Vida”. With them we shared not only our passion for sailing but also the fairly concrete idea that life can be lived in a more meaningful, deliberate and less consumerist way. Principles and ideas that, incidentally, had been tested very deeply during the prior weeks when the comforts of established society looked, to be honest, rather attractive.

Golfo de Penas is an unavoidable offshore passage, the intricate net of canals is interrupted by the Peninsula de Taitao and the route through them is only restored north of this massive peninsula. Choosing the right weather window can be hard, a mixture of feelings will try to take your better judgment away from you, the main one being that, for all intents and purposes, the southern adventure is over once you are north of Peninsula de Taitao. Sailing north of this big landmass means, basically, coming back to the human world, with all its evils and blessings: pollution, salmon harvesting floating nets, towns, loads of traffic and human activity, supplies, better weather, etc…

The anxiety is great for a crew that has been subject to exhaustion and a hardship that for several months was my case. When I chose the weather window, Martin, captain and owner of “Otra Vida” thought very plainly “that’s not a weather window, not for us, at least”. The expected condition had, indeed very nice and gentle winds, between 10 to 20 knots from the west and north west, so it was bound to be a slow but hopefully peaceful upwind leg. The problem was not the wind, though, but the waves: 6 to 9 meter swells expected from some storm that had developed miles away. This is an offshore passage and that means sailing day and night, in theory at least the possibility of using the self-steering system, but that’s when the waves destroyed all the fun.

The swells were not breaking (if they had been it would have been hell) but the mixture of huge swells and mild to light winds created huge variations on apparent wind between every trough and crest, furthermore, when you see a “weak” condition, that usually doesn’t mean that you’ll have a stable 10 knots, but rather that the atmosphere is in transition and the sky is torn with dark clouds and squalls followed by calms. Our passage was not dangerous, but not restful or easy at all and from the moment we made it north of the jagged, terrifying fangs of Cape Raper, we were very tired and ready to stop, especially with the awful weather coming in the next 24 hours.

We dropped anchors and shore lines in Caleta Suarez where two big fishing boats soon joined us to avoid the incoming bad weather. We attached Steppin’ to the fishing boats that were attached to each other and the usual seamen’s community soon developed “Come to have lunch”, “Let’s have dinner”, “Let’s drink some mate” and soon we were all friends, all partners surrounded by stories of salty fear, success or failure. The crews were resting, waiting, cooking, doing maintenance or preparing fishing gear and hooks.

I went down to the engine room of one of the fishing boats and found there the mechanic checking engine levels and parts, he looked at me and soon we engaged in a conversation, technical at first, human a short while after. “I was captain of a couple of boats,” he said, “but I had bad luck: a couple of serious accidents. I have been on boats all my life sailing these waters, all the canals and the offshore coasts too… I sank a boat once, we were fishing in front of Cabo Tamar, and the weather started to worsen, we took the gear in and ran to the strait for shelter, but it was too late, the waves were big, very big and were on our tail. That lancha was unstable, I knew it already. I had told the owner of the boat, but he said ‘its normal, just keep fishing,’ the boat started to roll a lot, with the waves, it was hard to control her, suddenly one roll didn’t stop, the boat just kept rolling and turning over herself, the bridge touched the water and I scaped through a window, climbed to the hull as the ship capsized completely, another man made it to the hull too, the rest of the crew, 4 people, disappeared underneath, trapped in the ropes and gear, some of them couldn’t even swim. The hard part, you know, is to call the families. I was the captain and I survived. After we were rescued from an island where we had drifted, I had to call the relatives, many of them were fishermen too, but sometimes it is difficult, very difficult to make those calls, not everyone understands the rules of the ocean.”

Steppin Out kept sailing north through the waters of archipelago de Las Guaitecas and Chiloe. Steppin’, Cris and I arrived undamaged and extremely happy the 23rd of April, 2018 to the beautiful city of Valdivia, where a small group of friends and family were waiting for us at the dock. The trip was over after we had sailed all the way from Eden, from Williams, from Argentina, before that from Europe and the States, from Mexico, Florida and, really, all the way from my childhood dreams.

One final word: writing this is merely an excuse to arrive to this moment, the moment to say thanks. The only way I can pay tribute to the people who made this actually possible is to write and tell the story, share the idea that with few material resources but loads of good friends and support, weird things can be done. It would appear that the main character of the story is me, this is an unfortunate yet unavoidable condition, but I was not alone on that boat, not only because I was actually not alone, but with us there was a huge amount of people pushing us forward and this was a massive team effort. This, to all of them:

To Em, my wife, who was my main land contact, weather provider and, more than anything, moral support, she is my love and the light in the dark moments, you can do a lot of crazy stuff, but nothing can be done with a lonely soul. To my crew: Mane, Nacho and Cristobal, It’s a very rare type of people who are ready to leave their usual lives for months to embrace a dangerous and uncertain adventure, even more rare are those who are able to go through it without loosing their nerve and killing someone (me, in this case) and more rare still are those who, after the journey say “I would do it again”, cheers for these three brave, reliable, crazy and inspiring sailors!. There was one unknown mastermind behind most of the weather relevant decisions, Rodrigo Stagnaro was the guy who I sent messages to everyday for five months asking each time “how do you see this, our plan is this and that, what do you think of it? What will the wind be doing?” and with admirable reliability he was always there with the precise, vital help. My huge thanks to Jose Luis Rosales, Ivan Penna, Richard Luco, Mauro “mi patrón” Carrizo each one of them provided intelectual, social or material resources that allowed us to continue our journey after being stopped by a legal wall in Williams. To the crews of the sailing school of Williams, s/v Saoirse, s/v Otra Vida, s/v Haiyou, s/v Jalan, s/v Chenoa, each one of them gave food, information, diesel, hope and friendship to a project that saw several dark moments. My thanks to Edwin Olivares, the magic hand in the south, the guy you wanna know in Williams. This project started many many years ago, and many many miles away, some friends are far but never forgotten: Don “Mr Dance” Bailey and the “beer crew” in Florida and the PHCC in Portsmouth, England, people who believe in dreams and have the courage to support them. The remarkable Sailing Club of the Universidad Austral de Chile, for providing the crew and the conviction that sailing can be different: Guys, never give up! To my parents and to my Valdivian family, for always being there and providing a home to a world tramp.

February, 2017 – I have the pleasure to say that our boat successfully completed the second Atlantic crossing of her life (as far as I know…). The boat behaved beautifully and, if the crossing was hard, was only because of the weather and my bad decisions, that Steppin helped to overcome. Here there is a little story of the crossing that may be useful for someone attempting the same route:

Well, this time things didn’t work exactly as expected.

As is usual for long passages, I downloaded as much weather as I could, which meant that we had 6 or so days of offshore prediction, more than enough to decide our game of approximation to the doldrums.

The north east trades looked rather weak and there was an important gap of calms straight south of cape verde, so I decided to head south west and run down pass longitude 30, east of which there was basically no wind. We had a very successful run the first twelve days. Slow, is true, but we enjoyed easy trade wind conditions with force 3 and 4. Enough to have an easy life onboard and get between 60 and 90 miles of daily runs. Not bad if you are eating well, without much shaking and without hard reefing.

Everything was fine and at the end of the first ten days we were almost complaining about the uneventful rythm of our days. But things were soon to change.

On latitud 3 degrees 30 minutes north and longitude 31 west, the horizon ahead of us lost its fluffy texture of white friendly and isolated clouds, and formed something that could only be called “the threshold of apocalipsis…” a black grey formation, as high as the eye could see, with thunder, lightning and rain. It got on our way like the wall that guards the south.

Calm… wind shift, darkness and… Boom!!, the usual explosive irruption of the first violent squall, a sudden gust of wind that pushed rain as hard as bullets and, within seconds, had the ocean turned into a turmoil of confused waves that shaked the boat in all and no direction, while I pushed sails down as fast as possible getting tangled, as it happens, with my harness line on every little deck fitting, making movements clumsy and slow.

That was the beginning.

“Just a cloud”, we thought, but it wasn’t just one.

The doldrums are not exactly calms, they should be described more like “useless winds”, for it is rarely an actual calm. Normally is blowing on the wrong direction, gaining strenght and dying again, just to restart from the opposite angle, last other 20 minutes and go to zero.

Normally my phylosophy would be “sit down and wait for stable wind”, but as it turns out, we were actually moving towards the west north west at speeds varying between 1 and 3 knotts… which is not nothing, specially when we had already sailed fairly far west to avoid the calms that we saw south of cape verde, at the beginning of the journey.

“Don’t cross the equator beyond longitude 30”, recommends the cruising guide, but we were already on 31, and gaining west thanks to a strong current. Unable to make any consistent progress, I started a battle to move south-east on every gust, to fight against the current on every squall. “It’ll soon be over”, I kept telling myself, but the first day went by, then the second, and the third… after the fourth day I had slept only a total of 9 hours, and my head was turning to mash. I was shaky, cold or hot, confused and stressed. Sometimes, after 24 hours, I was only able to gain 4 milles to the south and none to the east. The fear that not even with the south-east trades we would be able to fight the current started to eat me, and suddenly I couldn’t even sleep on the brief seconds when there was no wind at all, because my mind kept telling me that, if we drifted passed cape San Roque, there was no coming back.

The fifth day we saw a cargo ship passing, and the only thing that I thought of, was to ask for a weather forecast, which gave us no hope… once the ship was gone I thought “what an idiot!! I should have asked for jerry cans of diesel!!”. But it was the first ship that we saw in many days, so our chances of getting a new opportunity were rather scarce.

On the sixth day, we had made a total progress of some 160 miles through the calms (1.1 knotts average…), all of them to the south-east. This was a remarkable victory against the current, but it came with a huge price tag: I’ve had almost no sleep on a never ending battle and, whereas I was fading away real fast, the ocean had endless energy for the fight. Em tried to help by feeding me, comforting me, or providing her bulletproof optimism, but I’m the only one able to sail the boat and there was no way around it.

Suddenly, in amongst the clouds, another ship appeared in front of my eyes! This time I had no hesitation, stablished radio contact, ask for diesel fuel and the ship answered without much passion nor discomfort, 30 minutes later the “Celigny” passed at 12 knotts beside us, throwing three huge industrial jerry cans of fuel overboard, which we promptly recovered on their wake. 75 liters!, enough to take us across the whole ocean if necessary!! I thanked the ship profusely, and without further celebration, they dissappeared on the horizon.

From that day on, things started to improve, now I could rest and recover the lost distances motoring for a couple of hours everyday, sailing when possible and now finding the desire to eat, which I had completely lost, and the chance to sleep.

The calms and squalls lasted for two more days, eight days in total, and suddenly the current stopped too… I thought that it would gain speed towards the south (as it is shown on the chart), but it just dissapeard, as mysteriously as it had arrived.

South of the equator, the south-east trades started to blow and our longitude, that had painstakingly gained one degree to the east, it was now 30 degrees west. From there, sailing a fast sidewind run to Brasil was totally possible, and we made some of the best runs on the journey, with well over hundred miles a day, on stable, reliable winds…

We made serious mistakes on this journey and had, at the same time, uncommon bad luck. We should have sailed back east when we still had the north-east trades, and we should have carried enormous amounts of fuel. The current was hard to predict, as it’s not very well described on the literature on it’s position, nor intensity… But we were definitely too far west, on a weak and exposed position.

This is my fifth Atlantic crossing, but the learning curve is, still, fairly steep. I thank the gods of the ocean for giving a hard lesson but, at the end, forgiving the lack of preparation letting us pass, and thank too, of course, the crew of “Celigny”, who helped on an efficient and seamanlike manner.

Now Steppin is peacefully anchored in Jacare, Joao Pessoa, Brasil.

December, 2016 – Well… I guess it’s time for a little update!.

We keep our slow pace over the surface of the oceans and now we are heading south from Canarias to CapeVerde.

Right now we must be sailing with something close to 25 knotts and we spent the whole last night sailing only under storm sail, so probably there were some 30+ knotts… Of course we don’t have any wind instruments, so this is pure guessing game, and we may very well be sailing on 10 knotts now. It doesn’t matter, if we get some 3 knotts of progress and the boat is not falling apart, everything is fine. (happy with daily runs of 70 miles, very happy with 85 to 100 miles)

The last months have been amazing, we stopped in Morroco where we were a little concerned because Steppin Out is registered on the states, but a healthy indifferent from everyone towards the Trump joke (and his hostility towards Islamic world), gave us hope on human kind and the opportunity to learn about their wonderful culture, art and religion.

We visited the magnificent mosque of Casablanca were a guided tour helped us to understand both architectural and religious meanings.

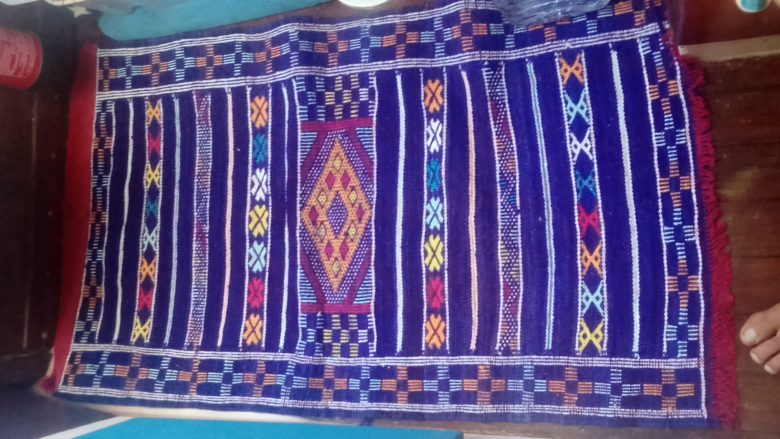

We even bought a little berber carpet for the salon of Steppin, mega posh!

Casablanca.

The engine is giving the normal little problems that are expected from any mechanical device and in Canarias I had to disassemble the water pump to change shaft and seals to solve a little leak of salt water, nothing serious.

Las palmas is the right place to play the doctor, because in case things go wrong, there are plenty of real mechanics to run for help. Apparently 1GM10s are prone to develop leaks on the water pump and I have seen some with the oil pipes under the water pump covered in grease for protection.

My most exciting intervention of the lasts months its rather unspectacular, but represent a huge improvement to avoid some of the last remaining leaks on the cabin: The handrails have been removed and reinstalled with aluminum laminated bases, so now they are really reliable to hold and completely leak free!! I’m so happy with that little silly thing that now I run on deck on every maneuver and stand on the handrails just to celebrate their strength!. Wonderful!.

Upgraded, custom deck handle holds. Mouted with aluminum laminated bases.

Other remarkable improvement was the shortening of the tiller. We sail the boat 99,9% of the time under self steering and, as we all know, the cockpit, when the tiller is down and swinging from side to side, becomes a little bit of a small battlefield.

We didn’t even have a comfortable place to seat because on our boat we built a sort of bridge deck on the front area of the cockpit. So one day I gathered my courage, the saw, and chopped some 6 inches of wood on the tip of the tiller. After that the cockpit felt immediately six inches bigger!!. Now I can even lay across the cockpit, is wonderful.

If hand steering is required, the remaining tiller provides enough lever to do so without problems and without hitting your knees with the end of it too. The length of the tiller, measuring only the wood, is 91 centimeters, and seems fine to me.

Upgraded tiller; shortened to give more room in the cockpit.

Steppin has been sailing easily and peacefully, as is expected from a strong boat under the rather undemanding conditions of the trade winds. We’ll make a brief stop in Cape Verde, and then keep sailing to Brasil, whose color, music and flavour are already attracting us powerfully.

We are hoping now for an uneventful and reasonably fast Atlantic crossing, being specially conscious of the possible calms on the doldrums area, for which we’ll be bringing loads of water, movies and patience.

Big hugs and fair winds for everyone!!

September, 2016 – Well, after sailing long time without an inboard engine on the boat, and having experienced scenes of traumatic struggle, floating for several days on a calm at plain view of the coast of Portugal, or tacking for several days on the calms or sudden gusts of Chesapeake bay, or heaving to for two days waiting for the 35 knotts of north wind to calm down to sail into Portsmouth, one starts to wonder… There may be something nice about having a little inboard that comes to our rescue from time to time…

Mainly the idea of sailing the south tip of south america, with all its gusts, fjords, little bays and big rocks, sounds very prone to cause death without a reliable engine.

We all know that the bristol 27 is not exactly a J70 to go tacking and maneuvering on tight spaces under sail. In fact, Steppin Out, graceful as she is on open water and rough conditions, behaves with a rather embarrasing lack of response on tight corners, and one remarkable episode almost saw us crashing against the notorious 60 footer “Hugo Boss” on a dock in Portsmouth (“I’ll sail close to take a picture”, I thought).

“I’ll sail close to take a picture”, I thought

The fact that Steppin will be, with all likelihood, my partner in cape horn made us take the desicion: Against our basic principles, we got an inboard diesel engine installed in England.

I bought a second hand yanmar 1GM10 and, in one month, dedicating some 10 hours a day, I got it installed with tank, shaft, exhaust, levers, bearing and so on. Every part was bought second hand or made by my very good friend and leith master Dave Bowyer.

The engine cost was 600 pounds plus our mercury 5hp outboard that the seller was nice enough to take as part of payment, all the parts and pieces were bought for other 500 pounds approx. Originally Steppin had an atomic four inboard so the main structures were there: the shaft tube and the supports, although the supports had to be modified a lot to welcome the new machine.

Needless to say, now our life is easy and comfortable, we even sometimes chose to motor through calms instead of just floating!!

Newly installed Yanmar 1GM10.

We already left England avoiding the arrival of a cold and windy winter, and Steppin presently floats on one of the many nice anchorages that the fjords of Galicia have to offer. We’ll keep moving south during the next months on our way to Brasil, Argentina and, eventually, Cape Horn.

Our monthly budget is something I would like to comment to, specially for the few that are planning on adopting a nomadic life on a boat. We spend about 500 to 600 usd a month. Making ourselves all the maintenance and never getting into marinas, our main spenditures are groceries, spare parts and hardware store items. Of course there are sometimes major economic disasters, like buying a sail, or this engine thing, but provided nothing goes too bad, the 500usd a month should be plenty.

I’ll keep in touch as always and if someone has any questions or need some further information, please write to my email!

Crew of Steppin Out

June, 2016 – It’s been a long time since my last post and a lot of things have happened:

After finishing the Atlantic crossing on Steppin out, we were asked to deliver a dufour 35 from spain to chile. The whole journey took us 4 months and on the meantime our boat stayed on the hard on the varadero of fuengirola.

The delivery went excellent and the panama crossing was an absolute highlight, a wonderful experience, not much as aan offshore sailor, but surely as a world traveller.

After arriving to chile we flew back immediately and, after doing the bottom paint, changing a thru hull and installing a new salt water pump for the sink (amazing luxury), we put Steppin on the water and sailed away, direction england.

In the united kingdom I have a big friendship with the Portsmouth Harbour Cruising Club, an amazing place for sailors, old salty stories, and cooperation.

Steppin out found a rather uncomfortable series of north winds and the way to england, with several stops, took us a month and a half. Our boat behaved wonderfully and finally we are now in portsmouth enjoying the peace of a long stop. We’ll stay here till the end of summer.

I haven’t answered to some of the comments that people have made and if someone wants to contact us, please use preferably my email address that I check all the time.

Cheers!! happy sailing!!

Steppin out found a rather uncomfortable series of north winds and the way to england, with several stops, took us a month and a half

Steppin Out, high, dry and safe in port.

July, 2015 – Bought her some three years ago and have lived on hers luxurious interior ever since then. We made a lot of modifications [to the rigging], like duplicating the shrouds, adding a babystay, a backstay and so on.

We are now in Azores, sailing from Mexico via New York and heading to Portugal, England and then south to Cape Horn and so on. The boat so far has behaved wonderfully and we do nothing but read and watch movies while we cross oceans on complete safety.

Here’s an inspirational image of Steppin Out in port, expressing that lovely small craft can-do:

Projects

Companionway Modifications & Hard Dodger

The companionway size been reduced since a long time. It was one of the first modifications I made. The horizontal, sliding hatch its fixed on its closed position and the lower board of the sliding boards is fixed too, to avoid an interior flood in case a wave fills up the cockpit. The entrance space is considerably smaller, which is usually found uncomfortable by tall or less flexible people, but it gives a lot of confidence in waves or under a capsize risk.

The vertical sliding boards are all fixed together and arranged on a sort of “door”, which makes it easy to close completely if conditions require it.

The rigid dodger was a new addition, specially for the trip to the south. It works fine on open seas, turns the cockpit into a way more friendly and dry area.When you are sailing the canals is sometimes uncomfortable because it does reduces vision and turns the “rock slalom” of the southern canals a touch more dangerous (but also a bit drier). I would definitely recommend it for long offshore passages, not for short coastal trips.

See the gallery above for images of Steppin Out’s hard dodger and modified companionway.

Comment Form